COMPOSITION

DESIGN

-

Turn Yourself Into an Action Figure Using ChatGPT

Read more: Turn Yourself Into an Action Figure Using ChatGPTChatGPT Action Figure Prompts:

Create an action figure from the photo. It must be visualised in a realistic way. There should be accessories next to the figure like a UX designer have, Macbook Pro, a camera, drawing tablet, headset etc. Add a hole to the top of the box in the action figure. Also write the text “UX Mate” and below it “Keep Learning! Keep Designing

Use this image to create a picture of a action figure toy of a construction worker in a blister package from head to toe with accessories including a hammer, a staple gun and a ladder. The package should read “Kirk The Handy Man”

Create a realistic image of a toy action figure box. The box should be designed in a toy-equipment/action-figure style, with a cut-out window at the top like classic action figure packaging. The main color of the box and moleskine notebook should match the color of my jacket (referenced visually). Add colorful Mexican skull decorations across the box for a vibrant and artistic flair. Inside the box, include a “Your name” action figure, posed heroically. Next to the figure, arrange the following “equipment” in a stylized layout: • item 1 • item 2 … On the box, write: “Your name” (bold title font) Underneath: “Your role or anything else” The entire scene should look like a real product mockup, highly realistic, lit like a studio product photo. On the box, write: “Your name” (bold title font) Underneath: “Your role or description” The entire scene should look like a real product mockup, highly realistic, lit like a studio product photo. Prompt on Kling AI The figure steps out of its toy packaging and begins walking forward. As he continues to walk, the camera gradually zooms out in sync with his movement.

“Create image. Create a toy of the person in the photo. Let it be an action figure. Next to the figure, there should be the toy’s equipment, each in its individual blisters. 1) a book called “Tecnoforma”. 2) A 3-headed dog with a tag that says “Troika” and a bone at its feet with word “austerity” written on it. 3) a three-headed Hydra with with a tag called “Geringonça”. 4) a book titled “D. Sebastião”. Don’t repeat the equipment under any circumstance. The card holding the blister should be strong orange. Also, on top of the box, write ‘Pedro Passos Coelho’ and underneath it, ‘PSD action figure’. The figure and equipment must all be inside blisters. Visualize this in a realistic way.”

-

Realistic Avengers action figures

Read more: Realistic Avengers action figureshttp://kotaku.com/5911846/these-avengers-action-figures-look-so-real-youll-think-theyre-tiny-actors

http://www.sideshowtoy.com/?page_id=37555&ref=Avengers2012

http://www.sideshowtoy.com/?page_id=4489&sku=9017301&ref=ref=avengersLP_9017301#!prettyPhoto/0/

http://animagetoyznews.blogspot.co.nz/

COLOR

-

Tobia Montanari – Memory Colors: an essential tool for Colorists

Read more: Tobia Montanari – Memory Colors: an essential tool for Coloristshttps://www.tobiamontanari.com/memory-colors-an-essential-tool-for-colorists/

“Memory colors are colors that are universally associated with specific objects, elements or scenes in our environment. They are the colors that we expect to see in specific situations: these colors are based on our expectation of how certain objects should look based on our past experiences and memories.

For instance, we associate specific hues, saturation and brightness values with human skintones and a slight variation can significantly affect the way we perceive a scene.

Similarly, we expect blue skies to have a particular hue, green trees to be a specific shade and so on.

Memory colors live inside of our brains and we often impose them onto what we see. By considering them during the grading process, the resulting image will be more visually appealing and won’t distract the viewer from the intended message of the story. Even a slight deviation from memory colors in a movie can create a sense of discordance, ultimately detracting from the viewer’s experience.”

-

FXGuide – ACES 2.0 with ILM’s Alex Fry

Read more: FXGuide – ACES 2.0 with ILM’s Alex Fryhttps://draftdocs.acescentral.com/background/whats-new/

ACES 2.0 is the second major release of the components that make up the ACES system. The most significant change is a new suite of rendering transforms whose design was informed by collected feedback and requests from users of ACES 1. The changes aim to improve the appearance of perceived artifacts and to complete previously unfinished components of the system, resulting in a more complete, robust, and consistent product.

Highlights of the key changes in ACES 2.0 are as follows:

- New output transforms, including:

- A less aggressive tone scale

- More intuitive controls to create custom outputs to non-standard displays

- Robust gamut mapping to improve perceptual uniformity

- Improved performance of the inverse transforms

- Enhanced AMF specification

- An updated specification for ACES Transform IDs

- OpenEXR compression recommendations

- Enhanced tools for generating Input Transforms and recommended procedures for characterizing prosumer cameras

- Look Transform Library

- Expanded documentation

Rendering Transform

The most substantial change in ACES 2.0 is a complete redesign of the rendering transform.

ACES 2.0 was built as a unified system, rather than through piecemeal additions. Different deliverable outputs “match” better and making outputs to display setups other than the provided presets is intended to be user-driven. The rendering transforms are less likely to produce undesirable artifacts “out of the box”, which means less time can be spent fixing problematic images and more time making pictures look the way you want.

Key design goals

- Improve consistency of tone scale and provide an easy to use parameter to allow for outputs between preset dynamic ranges

- Minimize hue skews across exposure range in a region of same hue

- Unify for structural consistency across transform type

- Easy to use parameters to create outputs other than the presets

- Robust gamut mapping to improve harsh clipping artifacts

- Fill extents of output code value cube (where appropriate and expected)

- Invertible – not necessarily reversible, but Output > ACES > Output round-trip should be possible

- Accomplish all of the above while maintaining an acceptable “out-of-the box” rendering

- New output transforms, including:

-

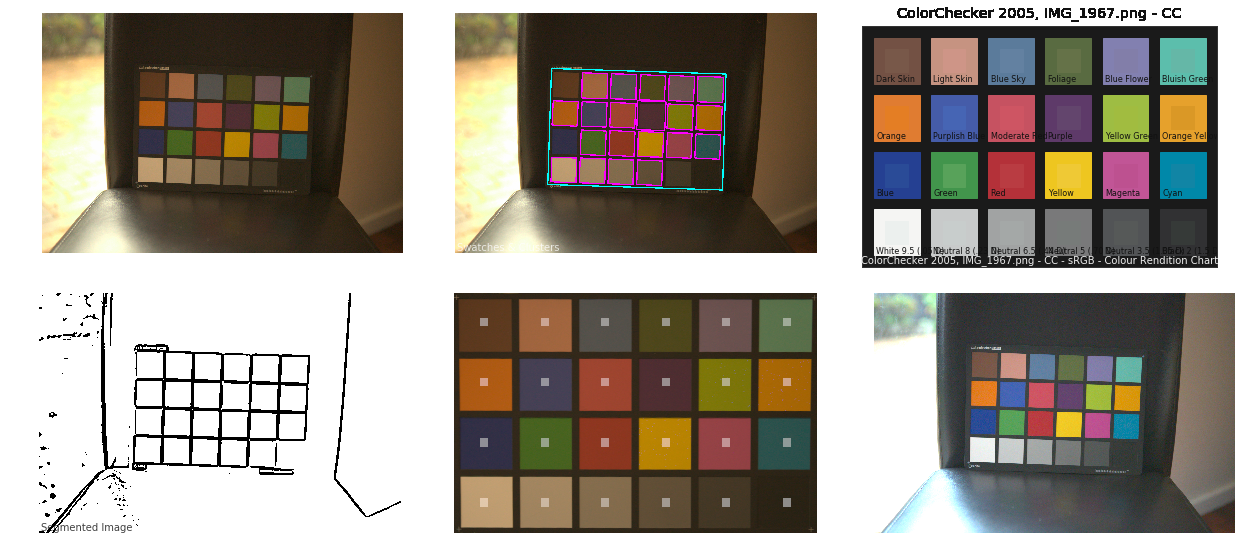

Colour – MacBeth Chart Checker Detection

Read more: Colour – MacBeth Chart Checker Detectiongithub.com/colour-science/colour-checker-detection

A Python package implementing various colour checker detection algorithms and related utilities.

-

What is OLED and what can it do for your TV

Read more: What is OLED and what can it do for your TVhttps://www.cnet.com/news/what-is-oled-and-what-can-it-do-for-your-tv/

OLED stands for Organic Light Emitting Diode. Each pixel in an OLED display is made of a material that glows when you jab it with electricity. Kind of like the heating elements in a toaster, but with less heat and better resolution. This effect is called electroluminescence, which is one of those delightful words that is big, but actually makes sense: “electro” for electricity, “lumin” for light and “escence” for, well, basically “essence.”

OLED TV marketing often claims “infinite” contrast ratios, and while that might sound like typical hyperbole, it’s one of the extremely rare instances where such claims are actually true. Since OLED can produce a perfect black, emitting no light whatsoever, its contrast ratio (expressed as the brightest white divided by the darkest black) is technically infinite.

OLED is the only technology capable of absolute blacks and extremely bright whites on a per-pixel basis. LCD definitely can’t do that, and even the vaunted, beloved, dearly departed plasma couldn’t do absolute blacks.

LIGHTING

-

Aputure AL-F7 – dimmable Led Video Light, CRI95+, 3200-9500K

Read more: Aputure AL-F7 – dimmable Led Video Light, CRI95+, 3200-9500KHigh CRI of ≥95

256 LEDs with 45° beam angle

3200 to 9500K variable color temperature

1 to 100% Stepless Dimming, 1500 Lux Brightness at 3.3′

LCD Info Screen. Powered by an L-series battery, D-Tap, or USB-C

Because the light has a variable color range of 3200 to 9500K, when the light is set to 5500K (daylight balanced) both sets of LEDs are on at full, providing the maximum brightness from this fixture when compared to using the light at 3200 or 9500K.

The LCD screen provides information on the fixture’s output as well as the charge state of the battery. The screen also indicates whether the adjustment knob is controlling brightness or color temperature. To switch from brightness to CCT or CCT to brightness, just apply a short press to the adjustment knob.

The included cold shoe ball joint adapter enables mounting the light to your camera’s accessory shoe via the 1/4″-20 threaded hole on the fixture. In addition, the bottom of the cold shoe foot features a 3/8″-16 threaded hole, and includes a 3/8″-16 to 1/4″-20 reducing bushing.

-

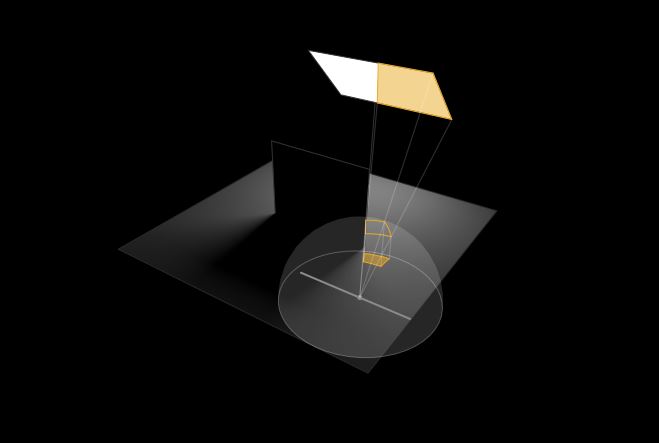

Light and Matter : The 2018 theory of Physically-Based Rendering and Shading by Allegorithmic

Read more: Light and Matter : The 2018 theory of Physically-Based Rendering and Shading by Allegorithmicacademy.substance3d.com/courses/the-pbr-guide-part-1

academy.substance3d.com/courses/the-pbr-guide-part-2

Local copy:

COLLECTIONS

| Featured AI

| Design And Composition

| Explore posts

POPULAR SEARCHES

unreal | pipeline | virtual production | free | learn | photoshop | 360 | macro | google | nvidia | resolution | open source | hdri | real-time | photography basics | nuke

FEATURED POSTS

Social Links

DISCLAIMER – Links and images on this website may be protected by the respective owners’ copyright. All data submitted by users through this site shall be treated as freely available to share.